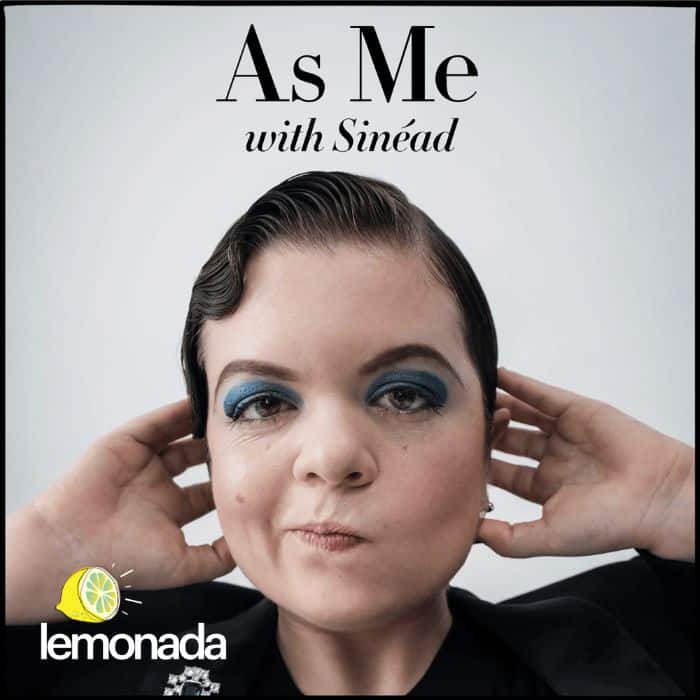

As Radhika Jones

Subscribe to Lemonada Premium for Bonus Content

Radhika Jones is the first woman editor-in-chief of Vanity Fair and the first person of color in that role. She opens up to Sinéad about what moved her to put her hat in the ring, and how she chooses her daily fashion armor.

Transcript:

[00:58] Hello from Milan. And welcome to this week’s As Me.

[01:03] Sinéad Burke: I’m here because this week I’m gearing up for Milan Fashion Week having just come off London Fashion Week, which as someone who has always wanted to be part of the fashion industry from well, as long as I can remember, it feels very surreal to say sentences such as those. London was wonderful. It’s always a city that cultivates the next generation of talent who we’re going to spend years talking about in the future. I got to see some wonderful collections from Victoria Beckham, who, if you haven’t yet listened to Episode 1 of this show, I recommend you do so, particularly this week when it’s so necessary to talk about kindness. I also got to see the Roksanda Ilincic show, which was so full of beautiful capes, fluid fabrics. And I got to sit beside Sandy Powell, the legendary costume designer; Vanessa Redgrave, the incredible actress; and Cate Blanchett, who one or two of you may have heard of. But also in London, I got to judge the International Woolmark Prize sitting alongside Edward Edenfield, the editor-in-chief of British Vogue, Hamish Bowles from American Vogue, and some incredible people where we decided upon who should be awarded up to $200,000 to really present their business in a sustainable way going forward, which is why now, in the middle of Fashion Month, feels like the perfect time to share the most incredible conversation with Radhika Jones, who is the editor-in-chief for Vanity Fair. We recorded it in New York and I have long admired her for so many reasons. First off, she’s the first woman editor of Vanity Fair. And in this conversation, she shares a bit about the decision to apply for that job.

[02:44] Radhika Jones: I knew that it would be a challenge to be more outward facing than I had ever been before. But I had a thought that I think a lot of us have at a certain point in our lives, which is, well, it’s gonna be somebody. Why shouldn’t it be me? And why shouldn’t I at least put my best foot forward and speak directly about what I think I could do?

[02:58] Sinéad Burke: Vanity Fair’s March spring style issue is out now with Anna de Armas on the cover. And if you’re wondering who is Anna, or why you should pay attention to her, previous As Me with Sinéad guest Jamie Lee Curtis is a mutual admirer of her. So if you need any recommendations, I mean, take it from Radhika and Jamie. So go get a copy and get inspired by the work that Radhika does. Are you ready for this week’s episode? Let’s go.

[03:36] Sinéad Burke: Sitting across from me is the extraordinary Radhika Jones, and I feel like I have to talk about how we met for the first time. I was sitting at a very long table, as were you, kind of around this time last year at the Green Carpet Fashion Awards in Milan. I had just won an award. I think my mother had paid somebody to give me that award. And I could see you down the other end of the table and I thought, “I need to go and say hello.” And I remember spending probably about 30 minutes rehearsing the briefest of speeches that I would later word-vomit at you, and introduce myself and say how admiring I was of you and how much I was a fan. And you were so kind in response. And I remember coming away from that evening feeling humbled and awed at your sincerity and gratitude. So I feel so lucky, Radhika, that I am sitting across you. Thank you so much for finding the time to do this.

[04:31] Radhika Jones: Well, I feel the same way. I mean, please recall that when we met, you had, as you mentioned, just won a big award. You had impressed and moved a roomful — and a very large roomful — of people with your words. And you do that all the time with your actions. And so it was a privilege for me to meet you. And it’s been so wonderful for me, at least, to run into you on the circuit over the past year, and catch up with you on Instagram now and again, the way we all do. And it’s one of the privileges, I think, of taking my job at Vanity Fair has been that in a very short amount of time I’ve made a lot of new friends, and new friends who are doing such amazing things, and you’re one of them. So it’s great to be here.

[05:11] Sinéad Burke: Well, thank you. The first question I would love to know is how do you describe yourself personally and professionally?

[05:18] Radhika Jones: I’ll start with professionally because it’s easier. I describe myself as an editor. And I’ve described myself that way for a long time. It’s the elemental role. It’s something that I feel is core to how I approach the world. I like to organize things. I like to curate things. I like to clarify and explain. I do that for myself. And I think that those are a big part of my role as an editor. And I also like to shine a light on things. And I’m used to the idea of being in the background, being a person who facilitates talent. I think those roles are important. So I think of myself as an editor first and foremost, and I also think of myself as a reader. And that, of course, goes back very, very far to childhood. And I don’t exactly know — my siblings and I are all huge readers — and I don’t exactly know why that is. It was just something that was in the water and in the air in my house. But I remember my grandmother, when I was very young, reading Oliver Twist to us at bedtime, and also reading The Merchant of Venice, which is a strange choice. I remember passages from the Merchant of Venice from being a child. And I think that I grew up with this idea that literature, and stories in general — that nothing was really beyond your grasp. That however old you were, you could aspire to read things that were complicated and think complicated thoughts and bring those ideas to other people. So those are the reading and editing and writing, which, of course, joins both of those things — that’s my professional identity. Of course in a way, it’s also my personal identity because it is who I am. So those three words maybe kind of circle around to describe me.

[06:55] Sinéad Burke: I’m really interested in this idea that as a child and as a young person, you were so confident in your ability to think bigger probably than your physicality. Was that ever challenged in any way by other people or was it just allowed to flourish within you?

[07:10] Radhika Jones: Well, in a funny way, maybe it was challenged by myself because I was also very shy. Perhaps I was busy thinking, I wasn’t necessarily busy speaking or demonstrating or acting. And so I’ve always had a little bit of that tension in my personality, but I guess I never felt that anything was particularly off-limits. And one thing that has struck me as I’ve grown older is how important that is. How lucky — I don’t know why that was — but how lucky I was to feel that way that, you know, things scared me. I would have to work up to something. It wasn’t as if I sailed through life with 100 percent confidence that I was going to ace every single thing. Not at all. It’s more just that I felt that I could try. And I think that a lot of the cultural conversations we’re having right now have to do with that, like, how has it been for people who haven’t felt that way, who haven’t felt that they have opportunity? And what are the things that we who have leadership roles in the culture can do to make sure that more people feel that way?

[08:17] Sinéad Burke: I think I’m very similar to you. Not that I’m editor-in-chief of Vanity Fair, but in terms of my childhood and beginnings are very similar, that I always believed I could, and that was reinforced by my parents and my family. Did you have people around you who mirrored that rhetoric?

[08:34] Radhika Jones: Oh, yes, definitely. My father, perhaps in particular. He had lived, in a way, a very unconventional life and a very artistically driven life. He had started out as a musician, to the chagrin of his parents, in the ‘60s in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was singing folk songs and organizing events at music clubs and things. And he pursued a career in music and he became a road manager. And he took some of the greatest artists of the 20th century around the world. He took Duke Ellington around the world and Thelonius Monk. And so he spent a lot of time in close proximity to greatness. And I think he felt very mission-driven to kind of be a person who could solve problems for them, who could get them literally from the airport to the stage with as little friction as possible. That was his role. He was sort of an interpreter. He was — anything that needed to be done, he would do so. He was a big troubleshooter. And also he was a great lover of music. And that’s what gave him such satisfaction and pleasure in his work. And then later, he became a director and producer of music festivals, and folk music and bluegrass were always a great love for him. So we grew up in a household where, you know, we went to school in a traditional way, and there were many traditional things about our family, but what my father did and the way that the arts affected his life, and the ways that we got to share in that, I think helped give me a kind of understanding of things like performance and working very hard with a team toward a deadline. Because when you’re producing a festival, you can’t push it by three days. You know, that is the day. And if it rains, by the way, it doesn’t matter, that is the day.

[10:22] Radhika Jones: And so I absorbed a lot of what I think now reflects back in my work, which is you collaborate, you come together for some sort of greater purpose — in this case, music. You try to touch people and move people through your work. And you approach your job with a sense of discovery. And one of my father’s greatest thrills as a producer of festivals was to listen to every single tape, at the time cassette tapes, that people would send him. He would put them on in the car during his commute and he would listen to every single tape that an up-and-coming musician sent him because he wanted everyone to have a fair shake. And occasionally he would find someone who might become a star, and he would book that artist. And he was always incredibly proud. Of course, he was proud to be able to showcase established artists, but he was, I think, incredibly proud to be able to bring more unknown, unfamiliar artists to a big stage, and help them on that first step toward acclaim and toward growing their own talent. So, I mean, of course, I never thought about it consciously as a child, right? You don’t think about those things. But in retrospect, I see that I absorbed a lot of that joy of discovery. And a lot of that has to do with developing taste and also with trusting your instinct. And so I saw that my father did that. He was not a person with many higher degrees. He was not, you know, he was — but his passion for music, and also his love of talent that was unique, was very infectious.

[11:53] Sinéad Burke: It’s so beautiful to hear that story. When you were younger, did you imagine or dream that this is the professional path that you would traipse down, or what did childhood Radhika dream of being and doing?

[12:07] Radhika Jones: No, so I didn’t know that being an editor was a job when I was younger. I knew that I would read a lot. I didn’t really think concretely about how that would manifest. And as a young adult, you know, in my early 20s, I began and eventually completed a PhD program in English literature, and I thought I would be a professor. Because that seemed like the kind of rational path for someone who loved to be surrounded by books. The funny thing about that is that at some point in my graduate career, a professor of mine was retiring and he invited some of his students to come to his office and take books off the shelves. And so of course I came in with an enormous bag because all you ever want is more books. And I start pulling them off the shelf. And he looked at me with this kind of tragic expression and he said, “you just love to read, don’t you?” I thought it was his way of saying like, this is actually not the profession for you.

[12:59] Radhika Jones: So but that was sort of my thought, was that I would be an academic, and that I would teach and that that would be the way that I would lead people through something that I loved, which was literature. But along the way, I moved abroad and I was living in Moscow and I started working as a copy editor at an English-language newspaper there. And I just kind of got the news bug. So I became very interested in journalism. It was a very newsy time, the mid-’90s in Russia. And I began to understand the adrenaline of working on a paper, and again, working with a team collaboratively and kind of bringing stories to light. So even as I was then pursuing my graduate degree, I kept editing. And I edited at a number of different kinds of magazines, like an arts and literary quarterly, and all sorts of things. And I just liked the deadline-oriented work, which is very different from graduate school, where you seem to just get extensions after extensions. And I like being in rooms with people and, you know, a PhD can become very isolating. You’re doing one now, aren’t you?

[14:08] Sinéad Burke: Yeah. I love and hate it.

[14:11] Radhika Jones: Yes. There’s a duality to it. So I was lucky because I got to be a — if I was having a good day with my dissertation, then it didn’t matter what happened in my day job. And if I was having a great day with my day job, then I could be sort of like not progressing much with my dissertation. This went on for years, by the way, which I do not recommend. Yeah, so when I was in my 20s, I started to figure out, oh, there’s this thing editing. And it’s a thing that maybe I would be good at.

[14:36] Sinéad Burke: And when you were doing the PhD in English literature, I’m often really interested in much like yourself, the stories that we tell, the voices that we choose to amplify. And historically looking at, I suppose, the select narratives that were chosen to be broadcast and to be made reflective of all of us. Were you conscious of the lack of diversity of voices that were in historic literature, or did you find material that you just reveled in?

[15:04] Radhika Jones: Well, I got around that by — I did a lot of work in contemporary fiction. You read all around, of course, right? And I actually have a great, great love for the 19th century British novel, which in its own way deals very much with kind of anxieties around race and class and all of the things that, you know, still drive our conversations today. It’s all there. You can see it there. But I also worked a lot with contemporary fiction. I had done some coursework as an undergraduate, and I continued as a graduate, in kind of the post-colonial literary boom of the ‘80s and ‘90s. And so I was lucky enough to kind of come of age academically when those books were very much becoming canonized. It felt I was studying at a good time because those issues were beginning to be aired. And I felt like we could be a part of that.

[15:56] Sinéad Burke: I wanted to draw on a point that you raised earlier about your father’s closeness to such geniality and such success. And you worked at Time. And you had such proximity not only to your own geniality, but to influential people that often you had a hand in curating or selecting or defining. What do you think makes somebody influential, or interesting or, you know, when you’re looking to amplify specific voices, like your father listening to the cassette tapes in the car. What was it for you in that era, and in the current one, that sparked something for you?

[16:36] Radhika Jones: Well, I was at time from 2008 to 2016. And in that time, so much changed about even the ways that one could be influential, right? You have the rise of social media and technology platforms that suddenly allowed people to have a voice. I think that for a very long time — well, Time magazine was founded in 1923, I think. And for decades, at least four decades after that, every week there was a person on the cover, otable person on the covers every single week. And there were writers and scientists and you know, people who it would be harder to put those people on a magazine cover now, but they were on the cover of Time because that was a standard bearer. But what I began to notice as I was doing things like working on the Time 100, which was a list of 100 influential people in the world, or working on the Person of the Year franchise, what I began to notice was that influence used to be much more tied to institutions.

[17:32] Radhika Jones: People became influential because they had risen to a certain point in an institution, or they had won a certain award or a sporting event, or they had achieved something in an arena that was agreed upon to be an influential thing. So that was how it worked. And you’d have surprises sometimes in those venues, right, but there were sort of traditional paths that would lead you to influence because you were at the top of something. And I think what has happened in the last decade and a half is that people don’t need those institutions anymore in order to be influential. The institutions in certain cases, I think, have lost some influence. Not in all cases, but the larger point is simply that you can become influential in a gazillion different ways. And so it makes it both more exciting and perhaps more difficult to figure out, well, what is real about it, right? Like is it a flash in the pan? Are there kinds of influence that are completely niche? How do you break out from those subsets? What is it that the culture can agree on? But these are all questions, I think, that are interesting for us in the tastemaking roles that we have. These are all questions that are interesting for us to pose, and provide some answers to, and at least have conversations about.

[18:50] Sinéad Burke: And speaking of influence and power and changing cultures, what or who gives you hope at present?

[18:58] Radhika Jones: Oh, so many people and so many things. And one of the things now that’s kind of core to what Vanity Fair covers — so I think about it a lot — is this idea that we’re living in an era of peak TV. Conceptions of old Hollywood have very much to do with the silver screen, the big screen, certain ideas about glamor and the studio system even, the business of Hollywood and how it ran. And I think as we’ve seen over the past couple of years, as the MeToo movement has risen, is that there were so many flaws in that system. I mean, many that we knew about, more and more that are being exposed. And it’s starting to change very drastically. And we’re starting to see so much more content because of the rise of streaming services and all of the creative energy that’s being put into them. And of course, what you can’t help but notice is that the fact that there are more shows being made means that there are more people who have the opportunity to be a part of them. And that’s on-screen, and it’s behind the scenes, and it’s in the ranks of agents and publicists and makeup artists and cinematographers and writers. And when I look at that landscape now, it feels so opened up. And there’s still a lot more room to grow and a lot more progress to be made, but it feels very different than it did even three or four years ago, and I think that is really exciting. And whether or not it shakes out and settles down and maybe contracts a little bit, I mean, I think we’re all following those stories and we’ll see. But in the meantime, when you have huge deals going to people like Janet Mock and Lena Waithe and Shonda Rhimes, it’s like these are storytellers who are really bringing something different to the table. And I think that’s good for the culture.

[20:49] Sinéad Burke: And as you said, with streaming platforms and different outlets being created, either through the Internet or through the landscape changing, we’re hearing different voices. Perhaps there’s a perception that through these platforms, there’s less risk, and that provides opportunity. And it’s how many young people can see themselves in television with Pose or with When They See Us for the very first time, and how does that shape their future? And it’s not your future, it’s your present. But as somebody who is quite humble and introverted as a person, what made you put yourself forward for editor-in-chief of Vanity Fair?

[21:28] Radhika Jones: Well, I got a call from David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, who, of course, I greatly admire. And he said that he was helping out with the search and that he had thought of me and would I be interested? And I love a challenge. And the thing is that, as I think about it, I mean that professionally, but I also mean it personally. I knew that it would be a challenge to be more outward facing than I had ever been before. But I had a thought that I think a lot of us have at a certain point in our lives, which is, well, it’s gonna be somebody, why shouldn’t it be me? And why shouldn’t I at least put my best foot forward and speak directly about what I think I could do? And so that conversation proceeded. But I just kind of made a decision not to — not only not to worry about it, but to kind of embrace it, and have fun with it. I thought this at the beginning and I think every day I think it more. Part of the value proposition of Vanity Fair is that it’s fun. One of our trademark properties is a party, the Oscar party. And so I feel like if I’m not having fun, I’m not doing my job. So every day I try to do both of those things.

[22:46] Sinéad Burke: And when David called you, what was your vision for Vanity Fair? How did you want to imprint upon it?

[22:52] Radhika Jones: Well, I thought a little bit about the history of it, and about how Tina Brown had kind of invented it when it was relaunched in the ‘80s, that she had made it this very buzzy, zeitgeist-driven magazine. And also had infused it with a kind of literary spirit and sensibility. I mean, she published — we think, of course, of her iconic covers of Demi Moore pregnant on the cover, and of photographs like Whoopi Goldberg in a bathtub of milk. And she made so many vivid images that stay in the culture. But she also published William Styron on the topic of his depression. She brought voices to Vanity Fair that were lasting and real and literary and delving into things that are serious. And the magazine has always had in its portfolio investigative journalism and reportage and photojournalism, even from warzones, as much as it’s had celebrity profiles and society and lifestyle reporting. And I felt in a funny way that my disparate experience — I had a little bit of that high-low balance in me, myself, and I thought I could bring that to the table. And I felt that there was room for Vanity Fair in the culture right now in this moment of change, because as I was having these early conversations, the reporting about Harvey Weinstein was just breaking. So it was becoming clear that things were being shaken up. It’s been clear that that is the case in Silicon Valley, very clearly the case in Washington, D.C. So all of these core areas were in a moment of flux that has continued. And I thought, well, what I would want to bring to the table is that zeitgeist sensation, that feeling of relevance, that feeling that we can still lead the culture by putting people on a magazine cover and telling their stories and making images that transcend the moment. It felt to me that even in this moment, in a media landscape that is very unstable and mercurial, that a property like Vanity Fair had the permission to be a strong voice in the culture. And I thought I could channel that voice. I could help be that voice. Lead the voice.

[25:06] Sinéad Burke: And you’re 18 months-ish in the role. What’s been your most curious day so far?

[25:14] Radhika Jones: Oh, my goodness. That is such a good question. There are some days where I do about six wildly different things, and I always — I tend to think about it — and you may appreciate this — in terms of wardrobe. So I look at my calendar the night before and I think, OK, what could possibly be appropriate to wear to breakfast with a photographer, a meeting with the CEO, an opening of an art exhibition and then, you know, whatever else it is. So there’s always something to wear.

[25:42] Sinéad Burke: What’s it like to live in your body?

[25:46] Radhika Jones: Well, I’m older than you, and I say that because it changes. It does change. And I had a child five years ago and that changes things, too. You know, it’s not something that I’ve had to think about all that much, which shows you that I have some privilege associated with it. I grew up very blessed to have a very fast metabolism, so I never dieted or anything. I didn’t really — I know it sounds obnoxious to many people who do, but I just — I was thin and that was kind of easy. But what I will say is that I grew a lot in my teens, and I never expected to be as tall as I am. I’m 5’11” and change. Sometimes I try to get away with six feet. But I grew a lot and I just was medium-sized for a long time and I just was kind of used to being medium. And then I suddenly was the tallest girl in my class. And it took me a while to grow into that idea. I didn’t expect it. And when you’re in your teens, and you’re trying to figure out your center of gravity — not only in your physical body, but also kind of morally, mentally, all of these things — it was disorienting. And I think as an adult, I mean, now I’ve been an adult for a long time, but as a true grown-up, I’m sort of happy that I went through that feeling of disorientation because I think it’s useful to absorb it. But I definitely see the advantages, of course. Another way to be easy to spot in a room.

[27:21] Sinéad Burke: Sadly, I get lost in crowds all the time, but that really works to my advantage. There’s such a thing called the Irish Goodbye, which means that you don’t say goodbye. I’m an aficionado at the Irish goodbye because nobody can see me. “Where did she go? Don’t know.”

[27:37] Radhika Jones: Well, my thing is that I’m nearsighted. I’m not terribly nearsighted. But everybody says, “well, why don’t you get the Lasik surgery?” And I say, “oh, no, no. Because when I’m speaking in public, it’s so helpful because I can’t really see anyone’s face.”

[27:50] Sinéad Burke: Well, I have three siblings who are optometrists. So if you ever need professional advice, you’re welcome to Dublin.

[27:54] Radhika Jones: No, don’t send them to me.

[27:57] Sinéad Burke: But speaking of advice, there are undoubtedly so many people who see you in your role and how you have transformed Vanity Fair. I mean, very recently we had Lupita Nyong’o on the cover with a profile written by Kimberly Drew. We had a best-dressed list that was diverse and reflective of society at large. And they dream of being someone like you, who is shaping culture and the world and society. What advice would you give them?

[28:29] Radhika Jones: First of all, it has been incredibly moving to me to hear those kinds of sentiments, from young women in particular. It does inspire me to make choices that are meaningful. And it’s just not something that I ever expected. And so I never take that for granted. And so I give these kinds of things a good amount of thought. I think one thing is it circles back to what we spoke about, about not thinking that something just isn’t for you, or that you couldn’t do it. And it can be hard depending on your circumstances. People internalize so much criticism or self-doubt. And that’s a serious thing. It’s not easy to overcome. But I do think that young women need to hear that they belong. That they are deserving of opportunity, that they can do it. And that they can be vocal about their strengths and about what they bring to the table. And I think we’re moving toward that as a society. But I think it can’t be said enough, because there’s so many places where I think from the teenage years on where it’s kind of easier to just take a quieter route. So there’s that. And then I often think about very practical things, one of which is figuring out in your own rhythms, when it is that you can get your work done. Because I think, I’m guessing you’re the same way, ultimately, one of the things that will help you succeed is simply hard work. And putting in the time and having a work ethic and maximizing what it is that you can do.

[30:12] Radhika Jones: I’m a morning person. And so, for example, when I was about a chapter and a half away from finishing my dissertation, and I was also working at magazines and I was super busy, I was in New York and and my father was ill. And I just there was a lot going on. And I got sort of frustrated and I thought, you know, I’m just going to drop the PhD. I don’t need it. I’m going to have an editorial career. It’s not necessary. I’m not going to teach. And I mentioned this to a sort of a new acquaintance. And she said, “well, I get it, but you seem like the kind of person who might regret that.” Which was somehow all I needed to hear. Sometimes you just need someone new in your life to kind of set you straight. Like she’d barely met me, but she figured that out. So I thought, you know, she’s probably right. I should at least try some sort of system. So I started waking up in the morning before I would go — I was working at the Paris Review literary magazine. So I didn’t have to be in the office until like 9:30 or 10:00. I would just get up in the morning and I told my husband he wasn’t allowed to talk to me. And I got to make myself one cup of tea. And I had an hour at the computer. And in that hour, I had to work on the dissertation. And that might mean taking notes on an article or book or writing, or I also had a dissertation diary in which I would sound off on all the terrible work I was doing in the actual document. And I had to kind of engage with it. And that’s how I finished it, because I found that time which worked for me. Now, that would not work for a lot of people. And some people work at night and they have to — and that’s particular kind of work. But I think that overall, finding a way to be productive, and tapping into your own creativity and energy, it really requires that you know yourself, and that you’re honest with yourself and that you set yourself up to succeed. Of course, we want everyone else to set us up to succeed, too, and we can work for that and fight for that. But I think if you don’t set yourself up in those simple ways, it’s harder to make everything else work. And so that’s my very practical thing that I think about is kind of like when can you do your work? And how can you make sure that you hold herself accountable for it?

[32:17] Sinéad Burke: Radhika, my final question for you: what do you want your legacy to be?

[32:24] Radhika Jones: There’s so much else that I want to do. I did finish my dissertation, but I haven’t written a book, and I would love to do some writing that was lasting. It’s what sustains me and helps me grow — obviously that’s a very broad statement. Merchant of Venice on, right? But I would love to contribute something to the world of literature. I’m a terrible fiction writer, so that’s off the table. So that’s a kind of life thing. And that would be the case no matter what else I was doing. I think at Vanity Fair, it is a good question because in a way it’s very clarifying in the day-to-day to think not just, OK, what are we doing today? What are we doing for this month? Who’s on the cover? How are we covering this particular thing? But also like, OK, if someone’s looking back on us 10 years from now or 25 or 30, take all the noise away, what is the message that we’re sending? What’s the bigger idea? I think that, you know, in terms of Vanity Fair, I would like my legacy to be that I captured a moment, a narrative in the culture and helped to develop it, and helped to complicate it, that we are a force for change and a force for cultural integrity. I want it to feel smart and relevant and I want us to be able to make a contribution.

[33:56] Sinéad Burke: Thank you so much. This was genuinely such a treat.

[34:00] Radhika Jones: Really fun.

[34:01] Sinéad Burke: I loved talking to you.

[34:06] Sinéad Burke: My favorite part of this conversation was merely the confidence that Radhika has in herself. As women, and as women who are perhaps from minority groups, so often the world tells us that we must be complacent or satisfied with the space in which we occupy. But Radhika’s kindness and strength and confidence by which she presents herself, well, it’s taught me to be a little bit bolder. Next week, we have a special treat for my fellow Great British Bake Off fans, Briony Williams. I’m excited to share our lovely chat from London, including her decision not to have any accommodations or accessibility made for her in the tent.

[34:47] Briony Williams: So before I went on the program, we sat down and we had a chat and they said, look, do you need any extra equipment, any special assistance? Do you want to be treated any differently, you know, how do you want us to approach it? And I said, I just want to be another baker. It doesn’t need to be mentioned, in my opinion. There’s no reason to do that. Just let me be, let me go in and bake against the others as I want to on an even playing field. They said, OK, that’s fine.

[35:11] Sinéad Burke: This week’s person you should know is reflecting on my time in London, at the International Woolmark Prize. The winner was Richard Malone, the first Irish winner of the competition. And I remember sitting with Richard maybe four or five years ago on some concrete steps in Dublin, and he told me, “women should wear clothes, clothes shouldn’t wear women.” But the reason why he was awarded the prize is because of his sustainable business model and looking at it as a circular economy. Paying the people who dye the wool and the craftspeople who’ve been working at this industry forever a fair living wage, but understanding that plants should be used as dye rather than chemicals. And really thinking forward about how do we create collections that are beautiful to look at, that inspire confidence when you wear them, but also are not harmful to the planet. He is a wonder. And if you’re not already following him on Instagram, do so right now. He’s @richardmalone.

[36:03] As Me with Sinéad is a Lemonada Media original and is executive produced by Jessica Cordova Kramer. Assistant produced by Claire Jones and edited by Ivan Kuraev. Music is by Jerome Rankin. Our sales and distribution partner is Westwood One. If you’ve liked what you’ve heard, don’t be shy. Tell your friends or listen and subscribe on Apple, Stitcher, Spotify or wherever you like to listen, and rate and review as well. To continue the conversation, find me on Instagram and Twitter @thesineadburke and find Lemonada Media on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook @LemonadaMedia.